Inspiration,

Process

Stephanie Metz

Inspiration,

Process

Stephanie Metz

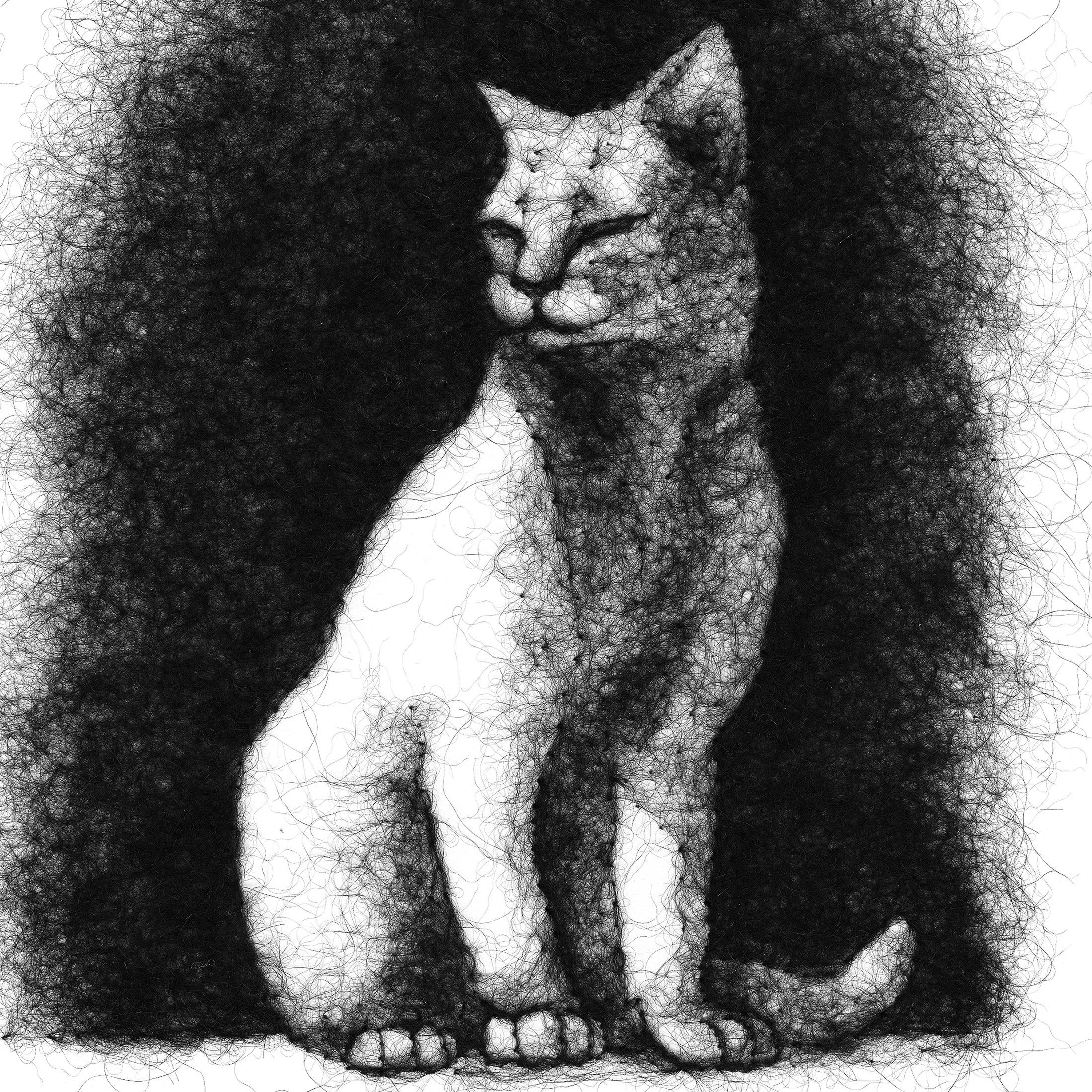

Answering Questions About Creativity: Being a Sentient Sponge

Latest Posts

Featured

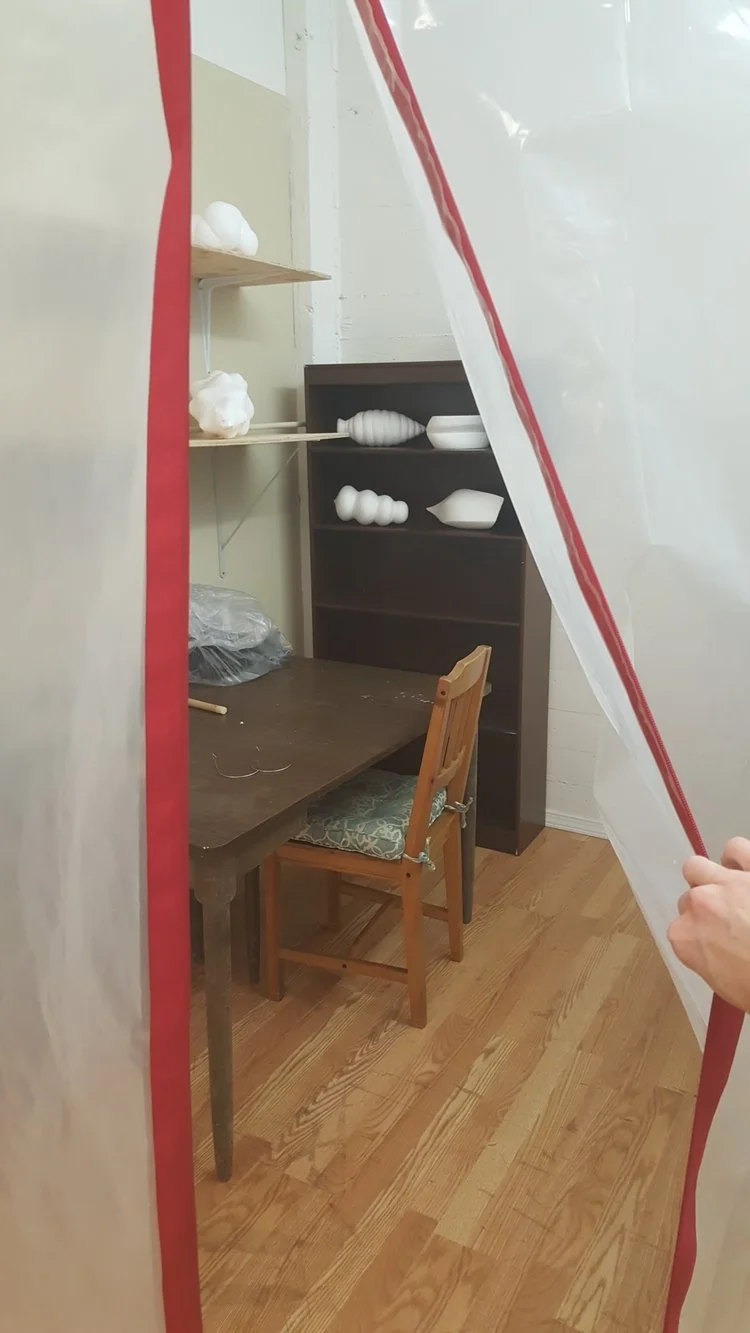

Plaster + Felt =?

![Words About Sculpture About Touch [Why I Keep Re-Writing My Artist Statement]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/588d00312e69cf76b7519a11/1738961418785-H0B3DY1FOGSHHLCTODVU/IMG_1562.jpg)