Stephanie Metz

Stephanie Metz

Professional Practices for Artists: The Gift of Attention and Time

![Words About Sculpture About Touch [Why I Keep Re-Writing My Artist Statement]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/588d00312e69cf76b7519a11/1738961418785-H0B3DY1FOGSHHLCTODVU/IMG_1562.jpg)

Stephanie Metz

Stephanie Metz

Words About Sculpture About Touch [Why I Keep Re-Writing My Artist Statement]

Stephanie Metz

Stephanie Metz

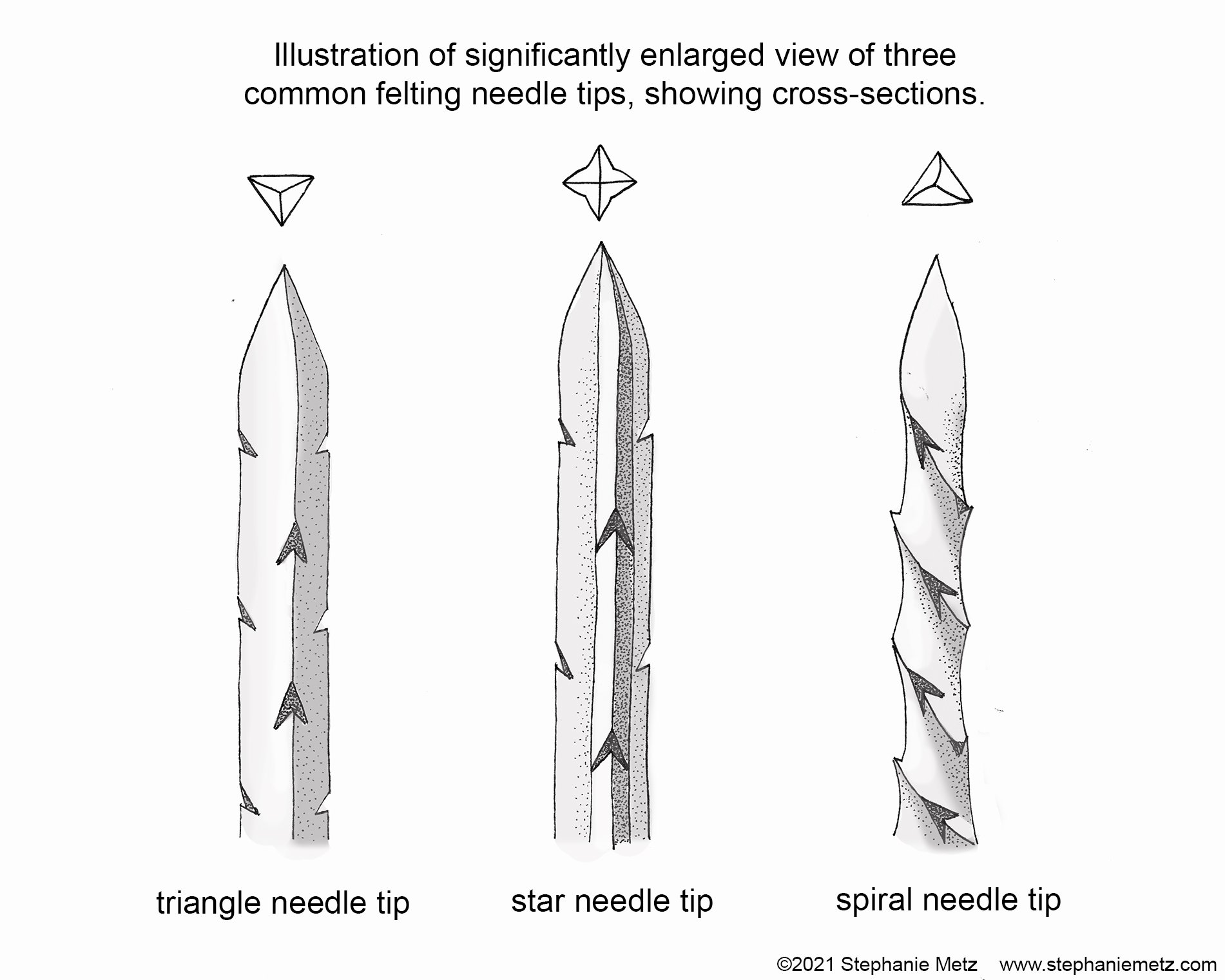

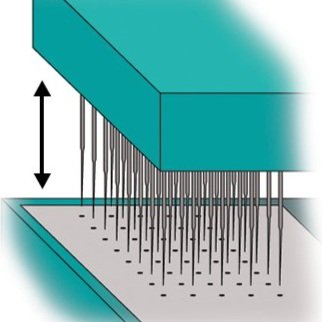

Simply Complex: Why the Simplest Marks Can Take The Longest Time

Stephanie Metz

Stephanie Metz

Why Visit An Artist's Studio? For The Little Things That Are Also The Big Things...

Inspiration,

Process

Stephanie Metz

Inspiration,

Process

Stephanie Metz

Answering Questions About Creativity: Being a Sentient Sponge

Events,

Inspiration,

InTouch

Stephanie Metz

Events,

Inspiration,

InTouch

Stephanie Metz

The Person Behind the Art: Summer Travel & Inspiration

Wall Sculptures

Stephanie Metz

Wall Sculptures

Stephanie Metz

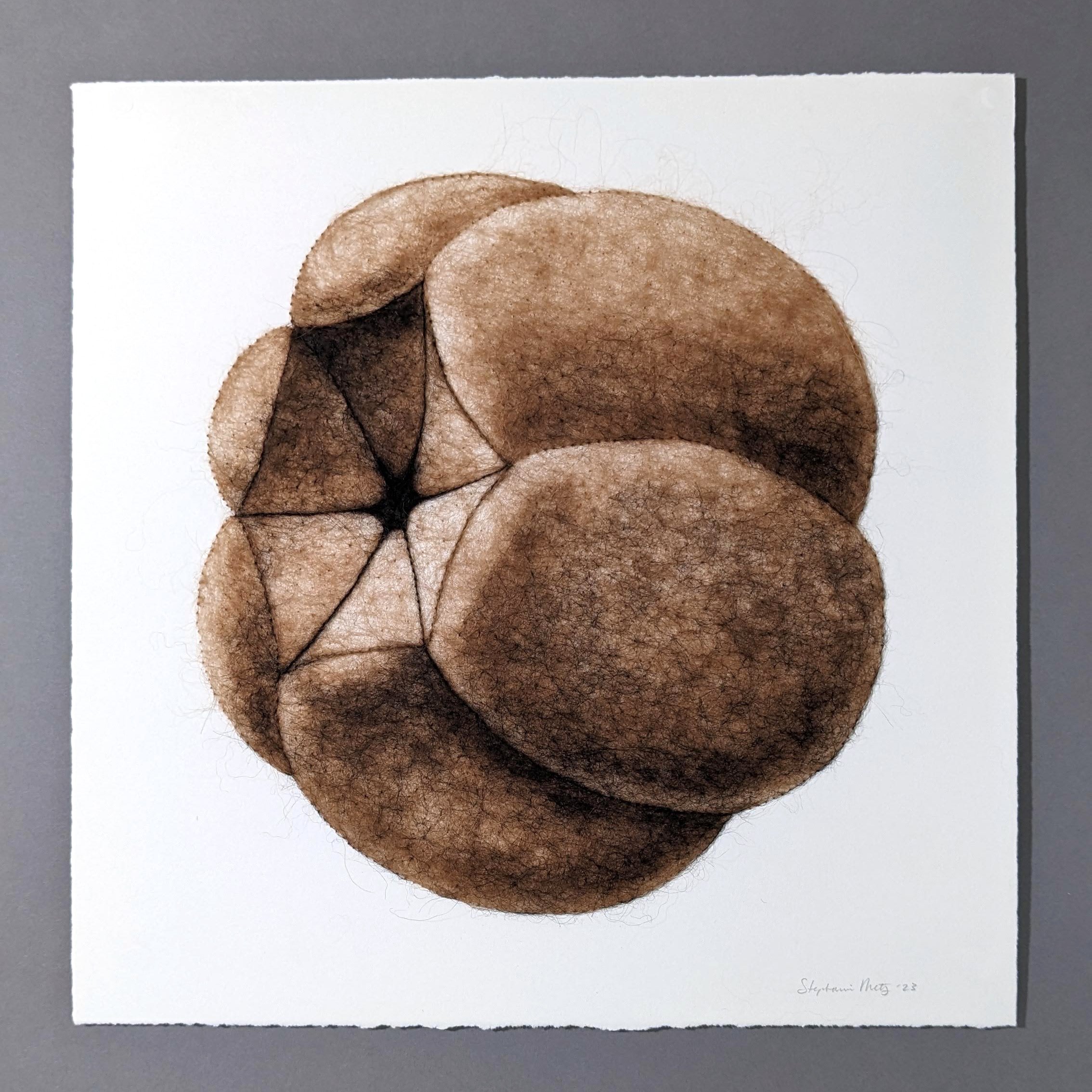

Stitched Industrial Felt Fiber Wall Art: The End of the Grey Curve Composition Series

Inspiration

Stephanie Metz

Inspiration

Stephanie Metz

Refilling the Well... the 2022 Yuma Symposium recap

Latest Posts

Featured

In the Glow: Behind the Scenes